Book Review: Almost Nowhere

How does King Crimson work? Wait, wrong series. How the FUCK does the Mirzakhani Mechanism work?

You may know the author of this extremely obscure piece of web literature: nostalgebraist. Before this, he wrote:

1. The Northern Caves: recently re-reviewed. For the lazy: it’s about an early 2000s book series’ forum meetup that goes wrong after they discover the dead author’s screwed up (and potentially paranormal) belief system. Infamous for its anticlimactic ending, famous for its otherwise stellar writing.

2. Floornight: a poorly-if-at-all-disguised riff on Evangelion, with an underwater base fighting against regular alien attacks and constant mindfucks. It’s got really likable characters. It also has a predictably terrible ending, but there’s no End of Evangelion equivalent to salvage it.

I recommend both of them anyway, though I’m more hesitant about the second.

So, Almost Nowhere has become his third major work.1 Here’s how long it took:

Incidentally, it took me three tries to actually make it past the first section of the book,2 after three (3) separate recommendations. Third time’s a charm? Not exactly. It more reminded me of the Jewish tradition where rabbis would turn away prospective converts three times to ensure genuine commitment. In some ways, finishing this book felt even more challenging. I think I was happy with my decision anyway.4

One more thing. As I was nearing the final chapter of act 3, the story itself addressed this introduction:

Maybe — on my third try with such a text — I will not bring a curse, but a blessing.

This is not a coincidence because nothing is ever a coincidence. Let’s go, reader, let me bless you with the tale of how nostalgebraist finally wrote a half-decent ending BUT also let me expound on the many cool and new flaws in detail.

The Overall Plot

Heavy spoilers follow. I do recommend at least trying this story, so feel free to read it before this, since even understanding the bare basics will spoil swaths of the plot. This summary might also be inaccurate in parts, since I’m only bilateral.

Almost Nowhere is a first-contact story that starts after the aliens have already won. The aliens (“anomalings”) are atemporal beings located in the fabric of spacetime (might very well be called a sentient aspect of that fabric), and have a high level of control over it. Their main hobby is (or can be interpreted as) painstakingly documenting every detail about it—without feeling anything in particular, being unable to understand symbolism and metaphor. Humans open up contact with the aliens, and the aliens are instantly disgusted.

Humans pervert the perfect physical universe with metaphor and meaning. Once the aliens know that a mountain is “like” another mountain, they can’t un-know it, and it is incompatible with their perfect records, their reason of existence. In addition, they’re beings designed for the cold, entropic end of the universe, and our “hot thinking” annoys them. This is somewhat reminiscent of the inferior novel Blindsight, or Crystal Society, if you’ve read that. A seemingly unbridgeable gap in how they process information.

Even if the anomalings could deal with our abominable point of view, humans’ reactions to the first contact have already harmed the aliens “retroactively” from their point of view. Atemporality means that a war has to start, because it’s already started in the future the aliens can see. The war is its own cause. The aliens kick off the war by trapping all of humanity in simulations of sorts called Crashes, think The Matrix, which “freezes” their thinking to more tolerable levels of temperature. This is as close as they can get to genocide.

We have a few main characters that the story shifts between:

Anne: a curious but inhuman child raised and experimented on by the “lead scientist” of the anomalings, Michael. Trapped in a simulation (“crash”) where she can interact with alternate selves of sorts. At least three of those alternate selves eventually become main characters of their own.

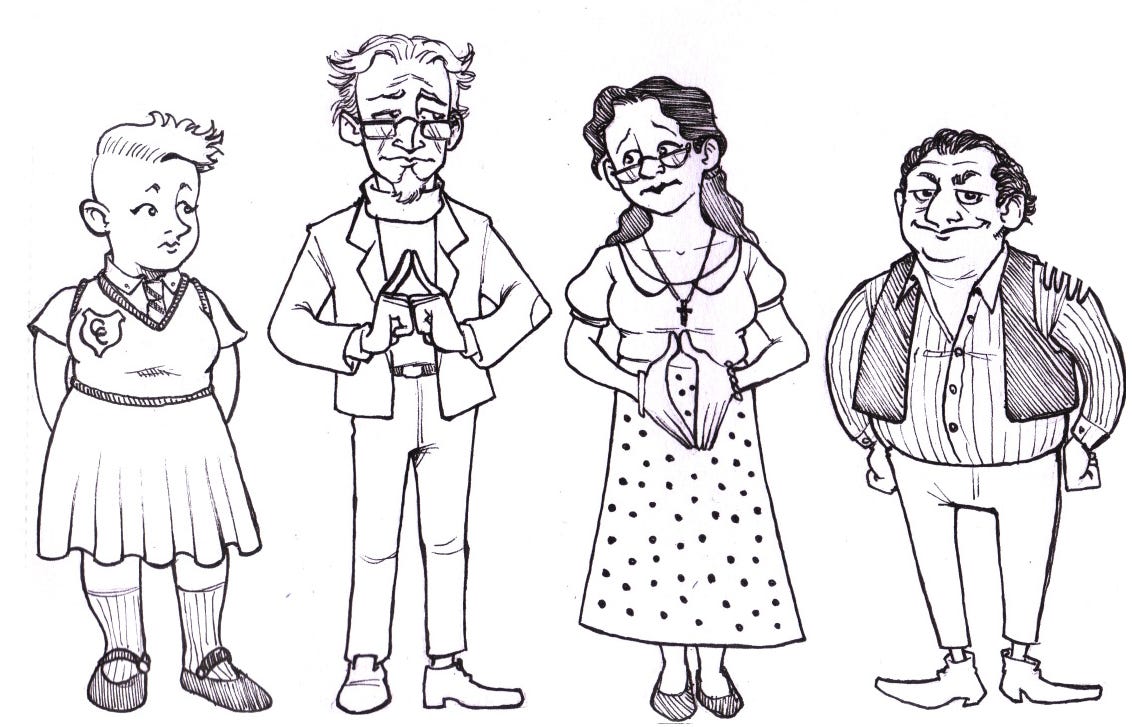

Some of the Annes after going through character… uh… development. Numbers unrelated to their age, it’s just their place in the sequence. Art by FIP Industries. Azad: the aliens’ favorite human and my least favorite character, responsible for translating the alien language to something we can understand, and vice versa. Frequently, smugly and verbosely takes over AN’s narration where it concerns anything alien.

Grant: the last human laboratory’s head of security, initially trapped with Azad in a different crash, but they split ways and he joins the “good guys”. The most “normal” point of view, our Jack Shephard or John Egbert, there to ask questions. In the Act 2 Advanced Containment Crash, he gets a dog, “played by” an anomaling, Sylvie, who ends up being more important and connected to the plot than we might have initially thought. Boy did Grant get lucky there

Cordelia: fanfiction writer turned fictional character in a Harry Potter-style series with the serial numbers filed off. That series has become a template for many human crashes set up by the aliens, since it’s a recognizable, relatively utopian setting. The school is run by Lucifer and Lilith, two fictional characters that become alien collaborators once they turn sapient. Cordelia sets off Act 1 by finding a device left behind by the lead human rebel, Hector Stein, after which she joins the “good guys”.

Cordelia, Lucifer, Lilith and Hector Stein. It’s worth keeping in mind FIP Industries, though a great artist, isn’t the best at remembering character descriptions. Cordelia has long dark hair, Lucifer’s short and spiky, and Hector Stein is meant to be african american, looking kind of like Laurence Fishburne, The Matrix’s Morpheus.

There are also a few interludes sprinkled throughout, concerning the “additional” characters mentioned and portrayed above and some randos.

Since aliens have complete control over the simulations, they can “rebase” them to completely restart them with different conditions, which they do multiple times (remember this, it’s important). This puts characters in different roles and mostly erases their memory,5 which helps make the story much easier to follow—wait no, the polar opposite of that, on at least four axes.

We see this conceptual war from the perspective of humans on both sides. Humans want to escape their simulations, with Hector Stein starting a group of rebels to hack them and get out. Aliens want humans to leave them alone, and their solution is to lock them away in simulations. The alien Michael is a bit of a wildcard in that he wants to find common ground, but he is inhuman and is just bruteforcing things with child abuse until they work. In Act 3, Sylvie genuinely becomes something of a human by spending enough time with them, and a new faction with its own unrelated motivations appears to complicate things further.

Through randomly ordered and eclectically narrated chapters, we get a gist of the progression of this war, and how characters react to it. Mostly the latter. Nostalgebraist loves his characters way more than he loves tight plotting.

That’s the bird’s eye view of the plot. I’d usually leave it there, but given that this story is extremely complicated and mired in Weird Time Shit, I’m going to summarize everything I can remember, chronologically, instead of the haphazard way things are presented (more on that later). Ready to get the entire plot ruined? Maybe, once again, try reading the story first?

A Detailed History

Welcome to our universe. It’s a place with a cruel mechanism known as Entropy: space start with a hot Big Bang, and through the laws of thermodynamics plus one hundred trillion years, eventually becomes a cold place with all the energy and matter evenly distributed. Time might as well stop, since nothing is going to happen. At least that’s how we understand it. Boy am I going to be embarrassed if a groundbreaking discovery dates this webfic review.

In Almost Nowhere, there is another aspect at work. Added to the fundamental forces, there’s the Mirzakhani Mechanism.6

See that diagram above? Each bar is a parallel universe. The MM is a force by which histories of “inferior” universes replace the history of the ones above them (the diagonal lines in the diagram). In the “hot” period and areas of the universe, this happens with small segments of time, at small scales. A single atom gets replaced with a slightly different what-if atom, some neurons get slightly different impulses. In “cold” periods and areas, mostly in the far future, the changes and timescales get higher and less frequent.

This process can be controlled by some beings, predicted by others. It’s a force with equations just like the others. Through half-handwave, half-physics lecture,7 this mechanism opens up some plot devices and worldbuilding details, setting up the plot. This is my understanding of it:

Thinking beings use the MM in their brains. Through evolution, neurons have learned to use the prediction of quantum universal changes as just another via of doing calculations. The Anomalings hate this “Mirzakhani-hot” behavior.

Some more advanced beings in the lower levels of the tree, the Everywhere-Heaven, have learned to actively harness this mechanism, and altruistically trigger butterfly-changes in the universe directly above them to create more of their kind of brain, and the process spreads, like a tree. Eventually they reach the “surface” timeline, the Almost-Nowhere, and their meddling creates less altruistic thinking beings, with only nothingness above. They’re protected nonetheless, since the Almost-Nowhere is the root all timelines split from, and without the beings at the top, the entire system falls apart.

The Everywhere-Heaven beings think this isn’t enough, it won’t last forever. Since they know their brains won’t work and they’ll die in the cold period of the universe, they decide to create something of a living subspace structure that will survive long after the universe begins dying. This is the “hive-mind” (kind-of) of the Anomalings.

The Anomalings hate the extremely hot and distracting Everywhere-Heaven beings, and ungratefully kill them all. Due to their atemporal thinking, it’s extremely easy for them to avoid feeling bad about this by excising the part of them that remembers the act. This is not a perfect process, and it creates Sylvie, who will become relevant only much later.

These aliens find humanity somehow (or viceversa, this part of the history is extremely confusing)8, the second iteration of everywhere-heaven-assisted beings. The process mentioned above makes them irrationally choose not to genocide again, so they’re going to try something new, an experiment where they cool brains in the Mirzakhani scale to make them more like Anomalings. Simultaneously, humans start trying to figure out how to communicate with these aliens in a secret facility.

The aliens use part of their own cold structure to “cool down” a giant machine they’ve built in a remote Earth location. They “clone” a child named Anne and put her in it. Unfortunately, they don’t think things through. If they cool something down, part of them will become hot, more human-like. This part “splits” and becomes the individual Michael, embodying the scientific desire of the anomalings to understand and control humanity.

Anne is stuck in this machine with Michael, exposed to his sort-of-AI-generated books and culture, trained to become the closest thing to an anomaling-human hybrid, so Michael can eventually “arbitrate” or mind-meld with her, figure out how to solve this conflict. Anne will eventually die, but Michael just clones another one afterwards. Time flies by faster in this machine, like in the average Dragon Ball hyperbolic chamber, and this helps Michael go through over a hundred Annes like candy.

Since these aliens are atemporal, and a MM-colder environment allows for weirder time mechanics, Michael puts a bunch of special “notebooks” in each Anne’s room that allows them to communicate with past and future Annes, most of which have had different lives and interests due to variations in how Michael and a third party have interacted with them.

This turns all Annes into intensely weird and inhuman little girls. (Sorry, it gets non-linear here) In the “future” of the plot, they’ll team up to defeat Michael’s child abuse, causing one of them, Anne 11 (which I’ll call “the singer” to avoid confusion) to escape early into the real world and trigger most of the plot.

Using future information, and to close a time loop, she manipulates a government employee of the secret alien-research facility into hiring Azad, a technically competent Persian translator who’s otherwise completely useless for this purpose.

Azad gives the aliens and humans words like “bilateral”, “arbitration”, “sign-train” and brings metaphor and color to what was until then a scientific and factual exchange of ideas. Though the process allows the aliens to learn how to use their structure to project bodies or “shades” of themselves into the real world, and how to partially communicate, they REALLY hate how Azad gives them nothing but pain, and it kicks off the next stage of the war.

They put all the humans in individual simulations (ignoring Michael, still with Anne in his own crash). These crashes take different forms depending on the human, but there are three important ones:

Michael’s Tower: the original Annes crash.

Mooncrash: this is an experimental human-made crash built by the alien-research facility, where Azad ends up locked up with Grant, the scientifically clueless but competent head of security. Largely irrelevant except for the way it helps them become friends and get in special positions later.

Hector Stein’s crash: like many others, takes the form of a Harry Potter ripoff where he’s “rebased” as a teacher, with only vague dreams hinting at his past life. Anne 17 (or “Annabel”), a technically minded Anne that also escaped her crash earlier, hacks into it with alien powers, and helps Hector start fucking shit up. The aliens decide to let him escape into the real world, since the crash system allows for temporal weirdness he really shouldn’t get his hands onto, and they kill Annabel. Years later, a Harry Potter ripoff fanfiction writer named Cordelia is put in this same crash. Later once again used as a rebel base of operations.

Act 1 revolves around these three simulations.

Michael finds the Mooncrash and puts Grant through alien education for some reason (the benefit of the audience, I guess, since I still don’t know why he did it),9 and eventually lets him go to join Hector in his asteroid base.10 Azad convinces Michael to put him in Anne’s crash, as a way to introduce Anne to human culture.

Cordelia manages to contact Hector from inside the crash, gets freed and becomes a simulation hacker under his employ, trying to free all other humans from their simulations. She briefly saves a specific Anne (“twenty-seven”),11 and loses her pretty fast, but not without revealing the real world to her first, which blows her mind and shows her how better life could be. This will drive her motivation to escape later on.

I think this is the best part of the story. Slowly finding out who the enemy even is, figuring out the nature of the simulations, meeting the characters… it’s before we get too tired of Azad’s personality too.

Act 2 concerns itself with the Annes and Azad in Michael’s crash, and the rest of anomalings finally creating a big, single simulation, “Advanced Containment”, where all other humans will be advancedly contained. Cordelia and Grant are married in it (the “rebase” ability to create alternate histories, remember?), and own a dog-played-by-an-anomaling named Sylvie, who keeps turning into a human and delivering opaque exposition. Hector has become a housebound gamer, haunted by Anne twenty-five (“Moon”), who also drives Grant into a video game addiction and pits them against each other in a xianxia-themed MOBAish game. These are largely useless details barring foreshadowing for a single major event later on.

After essentially losing her humanity by spending years on it, Twenty-seven triggers the “Nowhere To Hide” plan, which uses the notebook system to distribute a bruteforce attack on the overall Crash system. She really hates Michael and the anomalings, and will dedicate her many lives to fuck them over, down to retroactively founding the rebel faction.

This mostly looks like Anne 27 telling each Anne to try to move their arms n degrees to the left and do weird movements with their arms simultaneously until something weird happens, which takes decades off multiple Annes’ livespans. This works because the crashes are a buggy mess. Constant child abuse from Michael and contact with Azad has given them enough spite to want nothing but to kill Michael and escape.

The bruteforcing gives them a bunch of useful tricks, they’re essentially Neo from The Matrix. Four Annes escape: Moon, Eleven the singer, Annabel, and Twenty-Seven. The singer and Annabel escape into “the past” so to speak, setting up things we’ve already read. Moon spends her time hanging out with Hector in Advanced Containment, and twenty-seven and her will soon become his agents in the real world.

This was the nadir of the book. I’ll explain some of why later, but I basically only enjoyed certain parts of the Nowhere To Hide plan, and most of the rest had its consequences and development erased when the crash thawed.

Act 3 is triggered when Advanced Containment is finally broken, possibly by Sylvie acquiring godlike anomaling powers, possibly by Moon, possibly by Grant remembering his past, maybe all three. It was unclear to me, and the lead-up was so annoying that I don’t want to go back and check. All these things seem to happen randomly sometimes.

Now in the real world, Sylvie is firmly on the human’s side (with full access to the Anomalings’ powers), living with Grant and Cordelia. Twenty-seven and Moon are on Hector’s side, and humans are released onto Earth again.

Almost Nowhere does not concern itself with these uncrashed NPC, so we don’t really know how they feel about exiting a giant facility at the east coast of China.

Remember the diagram at the beginning of this section? Everywhere-heaven is finally taking a major role, it’s started reaching the top layer of reality and meddling with things. Animals like dogs and cats, who are technically thinking beings with brains and as such manipulable by EH, break into laboratories holding experimental brainwave-to-speech devices that allow them to speak. They start doing their subdimensional masters’ bidding and spreading their message (poorly).

The factions are muddled by now. Sylvie is essentially the main anomaling, and he’s on humanity’s side, still protecting the crashes from the animals, since he wants to preserve the lives of the “fictives” inside…

Sigh, I actually have to talk about Lucifer and Lilith now. The Dumbledore of the Harry Potter ripoff and his wife, they’re constantly involved in scenes as mild-mannered participants in conversations, but they don’t actually do anything. They’re like the main characters’ pets, which is a bizarre thing to happen in a story where an actual house dog becomes a godlike main character. Anyway, they’re using the anomalings’ “shades” system to keep bodies in the real world, and everyone loves them, mainly Cordelia, Sylvie and Grant, so they don’t want the final Advanced Containment machine to break, which would kill them.

This brings Hector and Sylvie in conflict, when they really should be teaming up against the everywhere-heaven beasts taking over Earth. A bunch of miscommunication and pointless infighting takes up big swaths of Act 3. I gladly welcome the fact that Azad is offscreen for most of it, busy translating the beasts at Hector’s behest and not ruining the narration as much as he has in the previous two.

A few chapters are dedicated to the everywhere-heaven launching a memetic virus right out of Snow Crash, spread via talking. The virus never affects any major characters, and is defeated by the beasts offscreen at the end of the act. I can’t begin to try justifying this narrative move.

While trying to defeat the beasts, unrelatedly, the Sylvie faction uncovers three important facts about the crash system:

From Annabel’s notes, they learn you can make “perfect” crashes that cannot be thawed.

From his experiences fighting against Hector in a video game in the Advanced Containment’s alt-history, Grant realizes Hector has figured out how to take advantage of the crashes by doing the same thing his character class does: savescumming. Hector intentionally uses crash rebases and people leaving them to actively change the past of the real world whenever something goes wrong. Humans can’t go back in time, but they can use the few alien structures that can send information back in time to effectively undo what just happened and give them more tries.

Azad and Grant realize the fact timelines are only “mostly” replaced means they could theoretically go to the oldest crash, Michael and the Annes’s, and, using Hector’s method, trigger a rebase that changes history before any of the plot happened, erasing all the pain they’ve gone through.

In the final chapter, the plan is put into action: Anne Twenty-Seven goes back to the simulation where she was raised, with the intention to change only enough things to make her life and others happy while keeping the stable time loops fulfilled. But she realizes halfway through that she doesn’t want a happy version of her friends, she wants her friends, and decides to keep everything exactly the same, except for a last conversation in her past self’s dream, sacrificing herself.

Simultaneously, Sylvie makes the existing Advanced Containment crash “perfect”, which forever saves Lilith and Lucifer and I guess gives humans the option to enter that fake utopia if they wanna.

And that’s it, no epilogues or anything. The story ends with the major threat defeated by a non-viewpoint faction, the big plan being changed last minute to do absolutely nothing instead, and the godlike figure creating a particularly good Matrix. That all sounds dumb, but I at least liked Anne’s final viewpoint and her motivation for doing nothing. A fully character-driven ending is better than the messes of the previous two works. I’m gonna give this ending a 7/10, and look forward to future nostalgebraistories.

You’ll notice it took almost the same wordcount to explain the “backstory” as it took explaining the actual plot. Yeah, Almost Nowhere is like that. All of these big events just happen between chapters, and characters largely react to them and/or explain why they happened, very artificially, sometimes downright cryptically.

The Bad

Getting Cute

There’s this conceit writers keep abusing, especially indie writers, and especially in the post-Whedon era.

They use clichés, a piece of bad writing, a plot hole, some characterization that doesn’t quite click. Then they make a joke that puts the spotlight on it. It inevitably raises the question: if you know it’s wrong, why are you writing it in the first place?

A complete chapter, written in an unmistakable style? In pure-cut Sylvie prose? Overwrought as shit, chasing its own tail down its own verbal mazes, losing the plot at the first opportunity?

It might have been funny the first couple of times writers did it, but just because Scary Movie and other parodies got away with it doesn’t mean the average story can spam it. Not without pulling you out of the piece of media you’re giving your valuable time to. Worse, after nostalgebraist gets tired of using the narrator for those “lampshades”,12 he starts abusing it in general, with little excuse.

Unfortunately, it seems to be the go-to tool in nostalgebraist’s writing belt:

What do you think of “Michael,” reader? Do you find something sympathetic in “his” quest for knowledge and harmony? Something a little charming in those very social failures?

Does that funny, halting manner of speech set you at ease, in a way? You’re used to the stock alien, after all, with prosthetic ears and no social graces. The other apes spurn him, but you are not so superficial. Your careful ear unravels the contortions of his speech. Your special love makes him into a real boy.

Have we made him a little too human? Maybe we have. A corrective is in order.

Reader, when you look at that blank stare, I want you to see lightyears of utter darkness behind it. Galaxies and black holes. The blank uncaring expanse of space and time.

“Uncaring” is too soft. Non-caring. Unrelated to care. Unrelated to you. Not for your consumption. It is an error that you are seeing this, and it will soon be rectified. Scheduled programming will resume soon. The cosmos is very sorry for the mixup, and you will be getting a refund.

“Galaxies and black holes” is too soft. You know what those are, or you think you might, or someone might, anyway. I want you to see stellar objects that no one has even given a name. No one ever will, either. They are not for you.

The nightmare is not your friend. Or your enemy, for that matter.

…

(How did I pull off this trick, you ask? Michael was a generous host, reader. He could transport other bodies hither or thither in crash-time, as easily as he could transport himself. I had only to ask, and he’d sling me off to whatever year, whatever moment my whims dictated. Nice to see you face to face like this, by the way, reader. It has been quite some time. Yours, Azad.)

…

We have a treat for you this time, reader! Just a little one, in the grand scheme of things, but we hope it will be diverting. Goodness knows we need something to lighten the mood, right about now.

Well, a treat for some of you, anyway.

Rest assured that we do appreciate the diversity of our audience, and do our best to respect it. We appreciate the gravity of our position, standing up here with our megaphone up on the biggest of all podiums. When we say “reader,” reader, we do mean you, most of the time — whoever or whatever you happen to be.

This little introductory device here is a rare exception. We’re speaking now to the earth ape sapients in the audience. The rest of you can read on if you like, but if you feel like skipping a few paragraphs to contemplate n-dimensional knots or something, we won’t hold it against you. We aim to please. If pleasure has no analogue in your inner lexicon, well, we still wish you the best, reader.

Now then, fellow humans! You’re about to see what no journalist was ever allowed to show you, at any point in the lurid years-long media narrative of advanced containment. An Almost Nowhere exclusive. We’re taking you right to the deepest heart of Management, where the real decisions got made. The place Eleven would no doubt call “the room where it happens.” (Have you met Eleven yet? No? What a shame. We’ll introduce the two of you soon enough.)

It’s relentless.13

Confounding Confounders

I’m sure you’ve heard of the famous Simpsons writing room quote:

One joke per joke, please

It refers to individually good jokes ruining each other when they’re put together in the same beat, saturating the viewers. I believe the same applies to what I’ll call “confounders”.14 They’re elements you intentionally put in your story to confuse and entice the reader. In Memento, the scenes are watched in reverse order. In House of Leaves, you’re reading a story inside a story inside a story. In Fight Club, one of the characters isn’t actually real, leading to a seemingly nonsensical progression of the plot.

So you might wonder how it would feel, reading a story that uses three confounders at once. Our protagonist has an imaginary friend he doesn’t know about until the end, but who drives the plot. His story is being read by another guy, and that guy is himself in a movie watched by a third party (actually, they also each have an imaginary friend). And the scenes all play in reverse order.

This analogy is not unfair, honestly. In Almost Nowhere, you have to deal with, simultaneously:

The previously mentioned narrator constantly taking over and injecting pretentious turns of phrase and references to erudite works.

Unjustified Alien Terminology: this one pisses me off in particular, because almost none of the concepts are actually that complex. The “translated” terms have an informed attribute of “being the only way of getting the ambiguities across”, but that’s just a lie. “Sign-train” is simply “message”, and any human could turn it into “story”, “book” or any of its variations in-context. “Arbitration” is the classic mind-meld from Star Trek or many other stories, but the story wants us to believe it’s near impossible for “bilaterals”15 (humans) to understand. No, nostalgebraist, we’ve had sci-fi for over a century. Trust me, we’re ready.16

There are no words in arbitration!!!! WE GET IT.

It’s a nonverbal form of communication.

Is that really so weird?

Like, of all the things you could say about arbitration, THAT’S what really gets you?)

[CORDELIA’s hasty penmanship.]17Time Shenanigans: the story is told non-linearly. Many chapters are out of order in some way, characters interact with their past selves, there are time loops involved, and the main sci-fi element involves parallel universes and Mandela Effect-style retcons.

Multiple characters and multiple worlds: you start chapter 1 and arduously get your mind around Anne’s weird living situation. Then you get to chapter 2, with a new main character, and an equally weird but different state of affairs. Then chapter 3 happens, and it’s even worse… but wait, halfway through the story, all those worlds get rebased into something completely different, too! If you’ve watched Rebellion, the Madoka movie, just imagine if we had Act 1 of that movie over and over, never being allowed to settle.

Near the end of the story, we discover that everything we just read is a “reconstruction” of events written by unreliable narrators. Which, I mean, is not really a twist given Azad explicitly wrote parts of it, but that could have had a variety of meta and non-meta explanations. I guess this doesn’t make the story more confusing as you read it, but it adds a retroactive layer of complexity.

The theme is characters failing to understand each other, I get it. You might have noticed most of the above applies to Homestuck, which has always been a big influence on nostalgebraist’s works, this time more than ever...18

Yeah, well, Homestuck is a visual story. You can see the characters.

I will give Almost Nowhere this, the character Grant is a masterstroke. He’s always there, asking the questions I want him to ask, stopping rants in their tracks and progressing the plot. He’s the MVP, and without him the story would be legitimately unreadable.

Passive Viewers

In a normal story, when a big event happens, the main characters are involved.

In Almost Nowhere, big events are only determined by the big players, who only rarely get any chapters to themselves. Viewpoint characters are largely reserved to being, well, viewpoints. A repetitive quantum-literary structure emerges:

Big event happens offscreen.

Characters react to it by having their new situation exposited to them by one of the big players. Worldbuilding walls of text ensue.

Big event happens offscreen.

Characters react to it by having their new situation exposited to them by one of the big players. Worldbuilding walls of text ensue.

Physics lecture.

Can’t let your guard down for an instant. Go to bed and wake into a new crisis which must be laboriously explained to you, entirely unlike every other before it, layers of fucked upon fucking layers. What is happening, what is happening, Hector, what did Hector do, which timeline is this

They are interesting events. Despite all the confounders, I can grasp what’s going on. I understand that with alien characters and the restrictions nostalgebraist has forced upon himself it’d be hard to have a viewpoint chapter that we can enjoy (and the story acknowledges it multiple times, see “Getting Cute”). But I still wish that he either tried harder or he let the more human characters be involved in the plot while we’re looking at them, especially because it skips over many character development moments.

The notable big exceptions are the Annes triggering the big plan, and Anne 27 at the end of the story. If anything, I’m missing a reaction scene after that one.

(Incidentally, I think this “flaw” might make Almost Nowhere pretty easy to adapt to any other format by an indie team. Maybe even a Homestuck-style fanventure, hmm…)

Repeated Infliction

I realize it’s a review crime to just quote another within your own, but I’m doing it anyway:

the last section gets a bit repetitive and it drags. it became saturating in fact, emotions did not let go for 60k words, alarm bells and claxons constatly screaming "THIS IS THE MOST IMPORTANT MOMENT, THIS IS THE CLIMAX, THIS IS THE MOMENT EVERYTHING GOES DOWN" for the length of what would be a standard novel. it wears thin. i can only sit though so many scenes of Sylvester loosing all hope and doing some ultimate gesture of final doom and then grant or lucifer say something moving or touching or inspiring or naive and then sylvie whiplashes again into benevolent omnipotent mania.

i can read the word love only so many times before it kind of loses its impact a bit, before it starts to sound robotic and rote. i see, eleven, yeah you truly love everyone, i get it, and you too animals, and silvye too, anyone else feeling omnibenevolent today? please make a line so we can reach the ending in orderly fashion.

The thing is, I don’t think this applied to Act 3 alone at all. Most of the long scenes are long because of repetitive turns like that one, not because of excessive content. FIP Industries, the reviewer above, had the privilege of following Almost Nowhere as it came out, with time to digest the repetition between chapters.19 Then, Act 3 came out really fast and they consumed it nearly all at once, so they only noticed it then. I didn’t have that privilege, I was dining at the all-you-can-eat Azad buffet with a time limit and complimentary pedantry.

To quote another reviewer:

If there's a criticism to be had, it's that sometimes Toby Fox doesn't know when to let a joke go.

Okay, that one wasn’t for Almost Nowhere, but it applies here, and not for jokes, for nearly every aspect of the novel. Nostalgebraist just isn’t good at being able to tell when to let Narrative Things go.20 An arduous arc with the audience trying to figure out what the aliens are saying? It will happen again with different aliens. 27 whining over being forced by predestination to do something? It will happen many times. Cordelia having an entire chapter about her Impostor Syndrome? Yep it’s happening again—

the repeated infliction of the wound — against anything but relapse, self-scarring, anything but the return to the site of the trauma . . .

Anything but? Nothing but.

Incredibly Specific Nitpick

Almost Nowhere has two ambiguous types of dialogue structure and it’s super easy to lose track of who is speaking! I haven’t seen this before, and I don’t remember happening in previous nostalgebraist stories either.

Type 1:

“So, that is a ‘no.’ I will not stop what I am doing, and I will not entertain further arguments about the matter.”

“But you have to stop,” Eleven sputters.

“Oh? Then make me.

Type 2:

“I’m sorry, Eleven. I do not quite catch your meaning. Could you say it again, a little more clearly this time? In complete sentences, preferably. And do take care to enunciate.”

“Nowhere to hide!” Eleven screams.

“34 After First Bloom, our special day! The little mouse you drew in my notebook, made out of letters, so Michael couldn’t tell it was a picture!

In the first type, a line break after the dialog tag means that the next non-tagged line is by a different speaker.

In the second type, a line break means the same speaker.

These two types coexist in the same conversation! It drives me crazy, and I can’t believe I’m the first person to complain about this.21 If there’s something that needs editing in Almost Nowhere first, it’s this.

The Good

Finally, some good fucking Content

Almost Nowhere is packed with stuff. Yes, I complained about it earlier, but the coin has a flip side, and it’s that you’ll never be bored, merely exhausted, sick of consuming too much hard-to-digest material, too fast. But sometimes things that are hard to digest are good for you.

Metafiction, truly alien aliens, the indomitable human spirit, communication and relationships, time travel, space travel, suspiciously reasonable fan-physics, the worst type of nerd given absolute power, post-alien worldbuilding… there are lot of aspects to play with in your head. The book is not exactly a pageturner, but it really makes you think, which is usually something I say ironically.

Character Stuff

As said earlier, nostalgebraist cares more about characters than tight plotting, and while it makes the action elements of the novel suffer, it means you have all the dialogue and emotions you could ever want. Some (probably insane) people love Azad, some (probably insane) people love to hate Stein instead of simply loving him, some others are inspired by the Annes’ story,22 identify with Cordelia’s fannish personality. Some, I assume, even enjoy Sylvie’s manic rants about his future trauma.

Even the Annes are different enough that they have fun interactions.

FROM [ANNE 27], NB 10, PG 3516

Hey Eleven, guess what? […] I asked for the record player and got it. As a machine, it enchants me. I think I will never tire of watching it in its hypnotic orbit.

As for the music? You are right, it is a revelation! It is now my constant companion. To think I read and wrote in utter silence, as recently as Last Green Leaf Gone. (It’s 43 After, now, in case you were wondering.)

I must be honest, though. (I try always to be honest, of course, but this next thing is the sort one prefaces with “I must be honest,” so brace yourself.)

I am mystified by your taste.

I’ve found all kinds of records to my liking — my favorites are the ones by Mahler, Shostakovich, and Glass (yes, really, Glass, yes, really, Glass . . . ), but I go in other directions too. Yesterday Azad played me some shrill thumping thing called Nirvana and, to my surprise, it struck a chord in me. (“Struck a chord” — I never knew what that meant! Now I do!! Life is full to bursting, isn’t it?)

But these song-stories, musicals, I simply can’t stand them. I gritted my teeth all the way through several records of Sondheim, and then did it all again with your other love, Miranda, who was even worse. I couldn’t get over the, hmm . . . I want to call it the shameless insistence of it all. Pulling you one way and another, and all the while braying with satisfaction about which way it’s taking you, as though it thinks you’re too dull to notice anything that is not spelled out in words.

Fake Physics

Long lectures about nostalgebraist’s extended Standard Model are a notable flaw of this story, at least allegedly, by like three other people who’ve read it. In all fairness, they get long. I’m talking over a hundred rarely interrupted paragraphs, around 7000 words of fictional physics to explain the Anomalings, and then in Act 3 there’s a similar paper to explain why the first guy got some things wrong, twice as long. But they’re great! I love reading about this kind of shit, especially when it makes some behaviors and twists click together.

There are even diagrams, sometimes!

Can anyone behold that LaTeX and deny the hard work that went into this novel?

I will say, though, that sometimes the powers are grounded on Themes and Character Arcs more than any logic or physical details. But it’s pretty hard to notice the inconsistencies unless you’re looking for them.

Better than the sum of its parts

The “Bad” section is much longer and more detailed than the “Good” section. Regardless, I think the balance is still slightly on the positive. The good parts stick around, the bad parts are quickly forgotten (in fact, when talking to the other three readers, I noticed they didn’t have a single memory of the sections I thought were the worst, nor the minor worldbuilding plot holes).

I’m going to commit yet another crime, and suggest skimming Almost Nowhere whenever you feel it’s going in circles. I know, incredibly disrespectful to Scorsese to watch a movie on your tellyphone, but who the fuck cares?

Sylvie talking in circles? Skim. Azad needing to preempt anything he says with sugar words? Skim. Anomalings in general saying things that almost make sense? Yeah nah it’s not a solvable puzzle, just skim and wait for a character to translate them with information you don’t have.

With this process, you’ll hopefully experience most of the Good the novel has to offer, and almost none of the Bad, without quitting the story early. Of course, feel free to read the story in Hard Mode if you’re able and you really want to, like I did, I’m not a cop.

Conclusion

Almost Nowhere is a lot.

I concur with the only other even-close-to-a-review there is, the one by FIP Industries I quoted earlier: I could criticize it for days (and I guess with this review, I literally have), it’s incredibly flawed, but in the end it’s so original that it’s a must-read nonetheless.

It takes much from Homestuck, The Matrix and a bunch of lame animes and visual novels, but I think it perfects some of the weakest elements from each.

Also, doesn’t this image make you sad? I might be the first person ever to review the full story instead of lightly liveblogging it. I mean, it doesn’t make me sad enough to create a Goodreads account, but maybe it’ll help you give it a try.

Almost Nowhere is available exclusively at Archive Of Our Own,23 for free. Go read it.

Lest we forget his minor work, some kind of weird Ulysses gay porn fic I’m sadly (?) not going to read or review. He also invented the famous nostalgebraist-autoresponder, who inspired Drewbot.

To quote nostalgebraist here:

All that said, I also want to caution against viewing the book as a puzzle you're meant to be able to solve on your own, like a "fair-play whodunit."

I intended it to be fun for the reader to wonder about how the questions will be answered, but there's no pretense of playing fair. And that "fun" is often more aesthetic and thematic than it is intellectual.

I hadn’t read this, and I did treat it as a fair-play whodunit, which made the first few chapters impossible challenges to set for myself.

The one that finally stuck came from Bavitz, author of previously reviewed Cockatiel x Chameleon, who is occassionally liveblogging it at his tumblr: https://weaselandfriends.tumblr.com/tagged/almost%20nowhere.

Extremely well adjusted readers with a rich social life will instantly recognize this concept from the end of Bond Breaker. It sounds like a joke, but nah, it’s pretty much what happens. Not that it’s that rare of a concept.

In this version of events, Maryam Mirzakhani lived long enough to finally complete the standard model with this final force. I think using a real life dead mathematician’s name is at the very least kind of weird, especially when in real life this really wasn’t her field as far as I can tell.

If you’re still confused, really want to understand, but don’t wanna read the entire story, you can instead check out the relatively standalone chapter XV for that lecture.

I think the timeline barely works out so that Michael creates the machine right after the anomalings are contacted by humans, then goes through ten accelerated Annes, the 11th escapes and sets up the translation part of the project. Around 130 Annes in 70 years, making it around 6 real time years between the start of the project and her escape, which seems like too long? I don’t know, I guess it’s not very important.

After talking to the writer, apparently it’s an underwritten aspect of the worldbuilding, wherein certain shades of the anomalings “guide” some uncrashed humans with anomaling ways of life as an alternative to keeping them crashed. But that plan is aborted when Grant is saved by Hector’s people, so it’s intentional that it leads (almost) nowhere.

It’s unclear to me whether Almost Nowhere is set in the future with advanced technology, or if the anomalings simply provided a fully built space station. The Everywhere-Heaven can arbitrarily give people better technology too, complicating things. Probably best to just relax.

Yes, YOU know she’s technically Anne 26 at this point, Almost Nowhere reader. I’m just trying not to confuse the already heavily confused normies.

I wrote this part of the review long before the others, and left quotes as a TODO, so I’m sorry most of these aren’t examples of “lampshading” per se. I don’t want to go back to the Azad mines. I beg you to let this slide. Also, to be clear, there’s nothing wrong with lampshading, it’s just the BAD-ON-PURPOSE type that’s bad (on purpose).

If you’ve read Homestuck: it’s like an eternal Doc Scratch intermission.

After some googling, this is apparently a pretty universally taught writing rule: if your concepts are complex, use plain language to explain them, especially in science-fiction.

This last one is lampshaded a bit early on, at least. But the aliens could have just called us humans (or Azad could have translated it as humans) and call it a day. That can be their new abominable word. Technically bilateral includes other animals, but then you can just use “animals”. Or even “life”.

And let’s not talk about the word “crash” itself, only a fool would arbitrarily pick that word to name something just because it sounds cool.

Nevermind, this is another example of Whedonesque lampshading, phew, review saved…

…

Nostalgebraist’s right behind me, isn’t he?

There are quite a few transparent references, by which I mean a Homestuck fan will instantly recognize them while a normie will not notice anything amiss. The cardinal opposite of HPMOR’s horrible, horrible Homestuck reference.

In the story’s defense, nostalgebraist did warn people to not try to marathon the novel, though his reasoning was more that the mysteries need time to percolate, and your mindset needs to stay synced to the viewpoint character’s.

In one of our conversations with him, nostalgebraist mentioned wanting Act 3 to be Almost Nowhere squared, all the parts of Act 1 and 2 at once, the most Almost Nowhere the story ever gets. Unfortunately, this probably magnified the flaws for some people instead of the good parts, which aren’t really food for magnification (except the Sylvie physics lecture, that one was a masterstroke).

Hopefully not enough to orchestrate a large scale investment scam, like that woman who was inspired by Worth the Candle’s Amaryllis. I fear what the real world equivalent of the Nowhere-To-Hide event would be.

I think it could find a small audience in Royal Road, confused why nostalgebraist is still releasing original fiction in ol’ AO3. Alexander Wales got deals with two different editors the moment he switched.