The Stand v. LOST

It's like Batman v. Superman, it's not a literal but an ideological conflict... either that or this essay is as trash as a modern Snyder film

Introduction

Before I go into why LOST1 and The Stand are secretly the same story (not in a lame “all stories are the Monomyth” fashion, don’t worry), here's a quick rundown on what's what.

The Stand (1978, re-edited in 1990) is one of the first novels by Stephen King, who needs no introduction.2

He wrote it as an ‘American response’ to Lord of the Rings. Instead of Sauron and orcs, we get the Devil-like Randall Flagg, the Jesus-like Mother Abagail and a pandemic that wipes out 99% of the world.3 The plucky immune protagonists first try to survive, then try to build a new society, and finally deal with Flagg's attempt to finish them off. Though I don't think there is a "point" to the five hundred thousand-word novel4, the themes revolve around organized society vs. chaos and Good vs. evil, with some "does fate exist?" thrown in, to which the answer is a boring “yes, next question”.

LOST (2004) is a TV show commonly and wrongly known as a big JJ Abrams5 project. He was involved with the pilot and basic concept only, with mainly Damon Lindelof6 and partially Javier Grillo-Marxuach7 developing them into a story proper, and Carlton Cuse8 restraining their most out-there urges.

A big international flight crashes into an apparently deserted island. The Island is anything but deserted: a monster, evil natives, abandoned laboratories all over... all tied to its special properties. After around a hundred episodes in, the survivors learn their plane crashed for a Reason, part of some kind of destined duel between opposing forces of Evil and Less Evil. Importantly, they were not dead all along, which is another Common and Wrong Belief.

You got it? Alright, let's go.

Ensembles of Crazy People

Writers often try some variation of this: come up with a main character first, make the villain a dark mirror or thematic challenge they must overcome, then add a supporting cast that shores up the main character’s flaws,9 fleshes out the world and adds mini-conflicts here and there.

Conversely, a lot of media, especially TV shows, go for an ensemble. Usually this isn’t an artsy motivation, but one of economics: the goal of TV is to put as many people in front of screens (and ads) as possible, and having one audience representative per demographic is a cheap way to avoid having to write universally appealing characters.

But ensembles aren’t always like that, and there’s something to LOST’s characters that fails to be replicated in forgotten copycats like Flash-Forward or Invasion.

Maybe it was because the ur-pitch, before anyone with talent got involved, was based on Survivor, a reality show. Whatever the case, the core concept came with many flawed characters as baggage, some with extremely abstract and unrelatable motivations or annoying personalities. In a regular show, this would have ended up going back to the drawing board, but the writers happened to go through a succession of unintentional swerves, and ended up with a seemingly generic “fake main character” to draw the people in and which allowed them to get the pilot greenlit. Jack Shepard was in fact so fake that he was once meant to die in episode one.

As cool a piece of showmanship as killing Jack in the first act would have been, I had serious doubts as to whether American network television would welcome a show anchored by a warped, frustrated middle-aged guy with delusions of grandeur, or an overweight Mexican, or a reformed Iraqi torturer, or a southern-fried con artist whose skills would have been essentially useless in the wild, or a non-anglophone Asian couple, […]

But for Jack, Lost seemed to be a series populated entirely by supporting characters: at least by the standards of our medium.

As Grillo writes above and later on, this is the key to the story-generating ensemble in LOST: not one of relatable main characters, but of awkward supporting characters that later get humanized in flashbacks. You may not relate to them now, but wait until you get to the episode where we see how they ended up this way. Even the seemingly abusive Korean husband, who doesn’t even get subtitles early on, is just doing his best to deal with his evil father-in-law’s demands. Conversely, Jack, who seems like the normal one (thanks to the abandoned gimmick), turns out to be just as crazy if not more than the rest. The audience anchor was never needed, it was never there at all.

It’s no surprise that Stephen King names Lord of the Flies (about boys stranded on a deserted island) as a formative work. The DNA for both works in this essay was there all along: some stories are driven by interesting conflict between very different characters, but you need an X-factor (like a deadly pandemic) in order to force it. The particular recipe both shows share, and which I’ll go in more detail in a different section: make many crazy characters, make their environment crazy, and shake the bottle.

While The Stand ends up presenting the same Crazy Ensemble LOST does, it didn’t have the benefit of foresight, because King wrote it without a plan, and he does so awkwardly, by putting the cart before the horse. When the apocalypse starts, we get more viewpoints than in A Song of Ice and Fire, each for a different flawed character10 as they deal with their own (often completely unrelated to the apocalypse) drama.

Maybe, if King had paradoxically watched LOST first, he would have skipped ahead to when everyone is dead and presented backstories in flashback form, that way readers get some tasty ensemble-driven storytelling from minute zero. The two works do share the jumping one-viewpoint-per-chapter structure, but the novel is missing that secret sauce, and the plodding 500,000-word novel makes pacing worse by burying the lede like this.11

LOST had a plan for the logistics of the formation of the ensemble. It’s a plane crash, so each flashback simply must answer the question “why did this character get on a plane from Sydney to Los Angeles?”. This has the additional bonus of allowing for more varied stories, from a man who tried and failed to look to a cure for a curse, to a brother rescuing his sister from an abusive boyfriend, to a woman in the midst of an extradition, handcuffed to a US Marshal.

The Stand, however, features dozens of characters who only end up meeting because of a shared dream, the aforementioned Jesus-like figure simply psychically guiding them so they come to her hometown. The characters are different, but many of their stories can be fairly summarized as “they go through small survival challenges as they make their way to Colorado”. With 99% of humanity dead, the old society is over, they have as good a reason to build a new one together as the LOST cast, so at least there’s no problem there.

This is not to say that the individual character stories aren’t interesting despite the repetition.12 We have a deaf guy who’s deputized to care over the bigots who attacked him as the lone sheriff of the town falls to the virus. We have the Trashcan Man, a serial arsonist who went through electroshock therapy and hasn’t been the same since. We have a man stuck in a prison cell as the guards die around him, and get to see his increasing panic at having to resort to cannibalism. We also have a couple women viewpoints, but this was 1978. I actually think these potential-flashbacks are the best part of the novel, to the point simply reorganizing them to break up the more annoying building-a-society sections would have benefited the overall pacing, better than the sum of its parts.

Like I said, if only Stephen King had the benefit of foresight—wait, he did, he rewrote the fucking novel twelve years later. I guess he’s just a hack.

Nested Act Structure and Themes

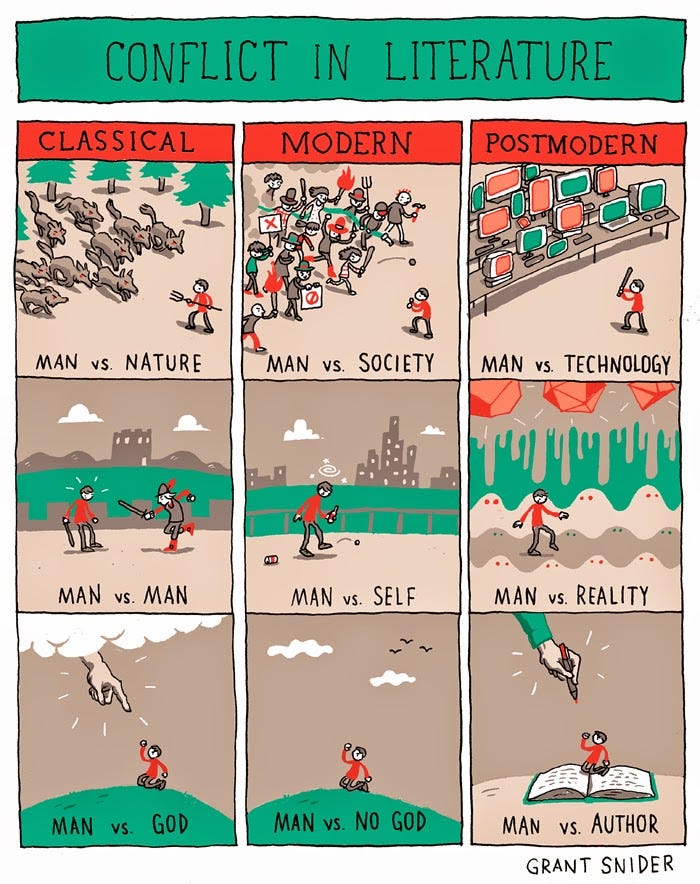

We’ve all seen this image:

Each of these squares is a theme that (often entirely) makes up the focus of a novel. Both LOST and The Stand, however, have three-part structures with varying foci, each of which would also qualify as a classical three-act novel or TV show.

And they’re, by pure coincidence I’m sure, exactly the same squares!

Man vs. Nature

I mean, this one goes without saying.

In LOST, it takes up the first season out of six. Many of the episodic plotlines deal with purely survival oriented motivations: Jack has to find freshwater or everyone will die. Locke has to hunt boars for meat or people will die. And of course, there’s always the matter of long term survival: though they don’t have such hot lives to return to, they think they want to leave the Island back to the real world. From the first episode and fetching the plane’s transceiver to the final episode’s sailing of a raft, the entire season revolves around this. By the end of the season, the characters have gained access to permanent supplies of food and medicine, and the challenge vanishes.

In The Stand, it takes up the first book and just a bit of the second.13 Almost every character is in a different part of the country, and they must make it to Colorado. This requires challenges like navigating traffic jams of cars filled with dead people, somehow performing an appendectomy with no operating rooms,14 or traversing long tunnels in complete darkness. Curiously, the nature of the apocalypse means there’s enough canned food in supermarkets to keep them going for a long, long time, so food is the least of their troubles.

The way my luck’s running the damn bike’ll be busted, Nick thought. No chain, flat tires, something. But this time his luck was in. The bike rolled easily. The tires were up and had good tread; all the bolts and sprockets seemed tight. There was no bike basket, he would have to remedy that, but there was a chainguard and hung neatly on the wall between a rake and a snowshovel was an unexpected bonus: a nearly new Briggs hand-pump.

He hunted further and found a can of 3-in-One Oil on a shelf. Nick sat down on the cracked cement floor, now unmindful of the heat, and carefully oiled the chain and both sprockets. That done, he recapped the 3-in-One and carefully put it in his pants pocket.

He tied the bike-pump to the package carrier on the Schwinn’s back fender with a hank of hayrope, then unlocked the garage door and ran it up.

There isn’t that much to say about these early sections, except that they’re very good and solid. Humans naturally enjoy survival stories, I think, for obvious evolutionary reasons.

Man vs. Man

Okay, everyone is together now. Our cast of very different characters is now together, their survival is almost guaranteed… unless their differing values fuck everything up.

In LOST, this takes up the brunt of the show, from Season 2 to the end of Season 5. We go through a succession of people trying to become leaders to the castaways—Jack, who has never wanted it from day one, Locke, who really has his own bullshit going on but doesn’t want anyone to leave the Island, and Sawyer, who’s a selfish douchebag without cause and yet who everyone turns towards when the former two abandon their posts. They have to deal with infiltrators in their society (the mysterious Others), with people who will betray their group, and when they find a cache of guns, they have to decide who gets to control it.

While the shifts from Season 3 to 4 to 5 change the “absent enemies that only attack at the end of the season” from the Others to Widmore’s Ship to the Dharma Initiative, the story is always most preoccupied with how the main characters decide what to do in response, how their individual goals clash with each other’s. This is most encapsulated in the conflict at the core of Season 2, where two camps are divided exclusively on whether to push a single button.

In The Stand, this is just Book 2. The characters make it to Colorado, and everyone is immediately split on whether to actually follow the religious Mother Abagail (who claims all that matters is fighting Randall Flagg) or have an actual democracy. Funnily, even though he’s writing by the seat of his pants, King goes into far, far more detail than he needs to, with many transcripts of council meetings, approvals of constitutions, and the like, which is lampshaded in the third book.

Among the odds and ends in his pockets, Stu found a stub of pencil, his notebook (all the Free Zone organizational stuff that had once seemed the vital stuff of life itself now seemed mildly foolish),

Less boringly, there are two sus saboteurs in town, there at the behest of Flagg, one of which wrestling with finally being accepted as “one of the boys” right as he’s about to betray them all. We also get a look at Flagg’s camp in Las Vegas, which has many of the same issues, as their chaotic leader is trusting some of the worst possible people to run things.

Man vs. God

Unfortunately, there always comes a point where you have to pay the check. Both works fall for many of the same pitfalls and it ends up leading to their bad reputations in the literary world.

In LOST, during the Season 5 finale, the man behind the curtain is revealed: Jacob. This is a guy with magic powers who touched every single character at some point in their lives, seeding them with inner conflict that led them to the island via serendipity-fiat. Why is he doing this? He wants someone to take over his job of protecting the island, because he’s both tired and unable to kill his brother, The Man in Black, who never gets a better name. I will note here that Randall Flagg often goes by the same moniker, in maybe the most obvious instance of direct inspiration. Jacob dies once all is revealed, leaving the survivors to deal with the problem alone.

The characters also have to wrestle with most of their lives being a lie. It’s their destiny to be here and beat the bad guy, or maybe they can refuse the call and join him. The mostly terrible Season 6 is filled with a roulette of “which character will follow/abandon the bad guy this episode?” as the writers suddenly realize that a literal 85% of the show’s runtime didn’t really deal with this main conflict at all, just some very vague “trust the island” vs. “trust le science” conflict presented to the characters through ambiguous dreams and visions.

I’ll get back to how the show eventually closes, but let’s talk about the novel first. Something I’ll get out of the way is that Randall Flagg is wisely introduced in Book 1 and shown throughout the novel, unlike The Man in Black in LOST. Even though our main characters don’t fully face him until the third book, we can give it that point over the show.15

More importantly, how many times did I say Stephen King wrote The Stand by the seat of his pants? Let’s let this quote speak for itself.

While writing The Stand, King nearly stopped because of writer's block. Eventually, he reached the conclusion that the heroes were becoming too complacent, and were beginning to repeat all the same mistakes of their old society. In an attempt to resolve this, he added the part of the storyline where Harold and Nadine construct a bomb, which explodes in a Free Zone committee meeting, killing Nick Andros, Chad Norris, and Susan Stern. Later, Mother Abagail explains on her deathbed that God permitted the bombing out of dissatisfaction with the heroes' focus on petty politics, and not on the ultimate quest of destroying Flagg. King sardonically observed that the bomb saved the book, and that he only had to kill half of the core cast to do this.16

This really has nothing to do with the act structure or my hilariously forced and oversimplified square system. It’s just bad writing. It “saved the novel” in that it allowed Stephen King to continue writing, that’s all.

Once the bomb goes off, Abagail gives four characters one final mission to go to Las Vegas and defeat Flagg. And that’s the rest of the book, a long walk there (they can’t take a car because God doesn’t like cars—I really wish I wasn’t only slightly exaggerating).

All but one character (cowboy Stu Redman, who’s left behind in the wilderness due to shenanigans)17 are captured by Flagg fairly easily upon arrival, and locked in a cage, while Flagg gloats about how he’s going to crucify them or whatever bad guys do.

They have no plan. They were just told to walk there by God via some random woman.

Okay, but they come up with one, right? Determination and adversity leads them to finally come together and defeat the villain?

No. The Trash Man, after a long, extremely drawn out adventure presented throughout the third book, shows up before the group with an atomic bomb. Flagg wanted weapons, right? He went find the biggest one.

I hear you thinking “the main characters then convince The Trash Man to rebel against his tyrannical master or figure out a way to blow up the weapon and take Flagg down with them”. If only. No. The literal Hand of God shows up and blows up the bomb for them.

Everyone dies, three main characters (again) and every villain in Las Vegas, a few of which we had also been following throughout the novel, and who never really get to do anything or develop much. I guess The Trash Man was always an arsonist who kept escalating, so that one is covered, but…

But I don’t want this to turn into a plot summary. I mostly want to explain and contrast that, while LOST repeatedly used The Stand as source of plotlines and maybe even the structural blueprint of the entire thing, it improved upon it. I’ll hinge more on this later.

In LOST, guess how they kill the Man in Black? Two main characters sacrifice themselves to temporary turn off the source of the Island’s magic shit, which also makes the villain mortal. Then another main character shoots him, with a gun.

It’s less fanciful. And they’re also making a leap of faith, without the characters being sure turning off the Island is at all the right move and mostly hoping it all works out. But they’re at least active participants in the events that take place, and ultimately deal with the problem themselves.

Bullshit and Conclusions

I admit it, I wanted the three people who made it here to continuously think I was reaching, so I saved looking for these quotes for last.

Carlton Cuse: For us, The Stand has been a model. Lost is about a bunch of people stranded on an island. It’s compelling, but kind of tiny. But what sustains you are the characters. In The Stand, I was completely gripped by everyone you [Stephen King] introduced in that story — how they come together, what their individual stories are, how they face the premise. That was such a good model for Lost.

Lindelof: The first meeting I had with J.J. about Lost, we talked about The Stand, and it kept suggesting ideas throughout the process. The character of Charlie was always going to be a druggie rocker, but when Dominic Monaghan came in to audition we started saying, ”What if he was a one-hit wonder?” I said, ”Like the guy in The Stand! The guy with just this one song.”

While I googled “did The Stand inspire LOST” halfway through the book and it made me keep taking notes in preparation for this essay, this is actually the first time I’ve read that admission. So that at least convinces me, and hopefully you, that I’m not crazy.18

The Stand was what the writers main go-to whenever they hit a snag, and it ended up accidentally taking over the shape and themes of the entire show.

This is, I think, because the writers started making it up as they went along. I know, the Javier Grillo-Marxuach essay basically entitled “The Writers Didn’t Make It Up As They Went Along” talks about how painstakingly they planned the first season and the episodic bread and butter structure. But Grillo left halfway through the second season, and even though Abrams similarly left the project early, he left his Mystery Boxes behind:

Because JJ’s calling card back then was the whole concept of the “mystery box” […]– he wanted the hatch in the pilot, even though no one knew what would be in it.

JJ was more than happy to punt the decision as to what would actually be inside the hatch to the writers' room because of his deeply felt conviction that the mystery was as good a journey as the reveal and would be so tantalizing it would keep the audience clamoring – even if the subject to be eventually revealed was not forethought. It was at that point that I first heard Damon articulate – wisely, and for reasons of self-preservation and sanity – the one hard and fast rule that he lived by for the entire first season. He would not put anything on screen that he didn’t feel confident he could explain beforehand.

For the entire first season, he says.

For example, while the idea was that the island called out to people and brought them in as part of a greater Manichean conflict, I didn’t once in two years and change hear the name “Jacob” or “the man in black.” The idea that people were being recruited to come to the island as part of this greater agenda was never brought up during my time on the show, even though by all accounts it eventually became the crux of the series' final arc.

Eventually, Lindelof became unable to continue rising up to the challenge of Abrams’ terrible mystery box philosophy, and, more and more often, started using The Stand to plug the holes.

This makes it impossible for any LOST fan to read the novel and not often go “wait a minute, I have seen this before”.

And while I’ve certainly used negative vocabulary while talking about this, I actually think it worked out for the best. There’s no loser in this “conflict”: Stephen King and Damon Lindelof were gushing over each other’s work in that interview above, Superman and Batman’s mothers are both named Martha.

LOST redeems all of The Stand’s terrible decisions, now tempered with hindsight, and when it “steals” things, it makes them better. I recommend the show, I don’t really recommend the novel. If only it had had a good ending to steal.19

If we’re to learn something from this, beyond “yes, watch it”, it’s that inspiration is a two-way street. The show gets ideas, the book gets redemption. Keep that in mind if you ever write something.

I swear this is my last LOST article for the foreseeable future.

That said, don’t think you know him if you’ve only watched The Shining, because Kubrick ignored most of the novel when he made the film.

You keep expecting for the bloated bodies to get up and become zombies but they never quite do.

I hear this is usually the case with Stephen King. He just starts writing and at some point he stops. It’s a bit different with The Stand since he got the opportunity to rewrite swaths of it, but he mostly added new stuff and updated the setting to the 90s instead of the 70s.

Known for Alias, the new Star Trek movies with young actors, and Rise of Skywalker.

Known for The Leftovers (which I dropped after one or two episodes, but I’ve always wanted to come back to) and the Watchmen TV show (which I haven’t watched and Alan Moore hates, but Alan Moore hates everything).

“Known” for the Cowboy Bebop Netflix live-action remake, but I swear he’s good here. He is, to me, the most remarkable of the many writers that stood up to producers, and came up with sci-fi ideas that “derailed” LOST into the masterpiece it became. I will heavily quote him in particular because he wrote this essay that details the story of how the show was made.

One go-to approach is a Freudian Trio, like Shinji, Asuka and Rei or Harry, Ron and Hermione, and another is the Four Temperament Ensemble, like the nerds of The Big Bang Theory. These sound arbitrary prescriptive, but they’re local minima that many writers are drawn towards naturally.

Stu Redman, the cowboy-like small town everyman figure, is the closest The Stand gets to main character status. While the first chapter features him, it’s only as part of a group of equally fleshed out people sitting around a gas station, and the character has no way of knowing he’ll be the only survivor. He’s described as a quiet, boring man. The book quickly moves on to a different viewpoint character before it reveals anything else.

Of course, you can say that Stephen King simply wanted the ol’ Hitchcockian “showing a bomb underneath a table of unaware people” as opposed to presenting a mystery. In fact he literally does this later on. But it’s a bit dragged out, and probably made worse by the lengthened re-edit—we even get to see military communiques in full as they try and fail to contain the pandemic, which I guess is at least interesting.

COMMUNIQUE 771 ZONE 6 SECRET SCRAMBLE

FROM: GARETH ZONE 6 LITTLE ROCK

TO: CREIGHTON COMMANDING

RE: OPERATION CARNIVAL

FOLLOWS: BRODSKY NEUTRALIZED REPEAT BRODSKY NEUTRALIZED HE WAS FOUND WORKING IN A STOREFRONT CLINIC HERE TRIED AND SUMMARILY EXECUTED FOR TREASON AGAINST THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA SOME OF THOSE BEING TREATED ATTEMPTED TO INTERFERE 14 CIVILIANS SHOT, 6 KILLED 3 OF MY MEN WOUNDED, NONE SERIOUSLY X ZONE 6 FORCES THIS AREA WORKING AT ONLY 40% CAPACITY ESTIMATE 25% OF THOSE STILL ON ACTIVE DUTY NOW ILL W/ SUPERFLU 15% AWOL XX MOST SERIOUS INCIDENT IN REGARD TO CONTINGENCY PLAN F FOR FRANK XXX SERGEANT T.L. PETERS STATIONED CARTHAGE MO. ON EMERGENCY DUTY SPRINGFIELD MO. APPARENTLY ASSASSINATED BY OWN MEN XXXX OTHER INCIDENTS OF SIMILAR NATURE POSSIBLE BUT UNCONFIRMED SITUATION DETERIORATING RAPIDLY XXXXX COMMUNICATION ENDS

GARFIELD ZONE 6 LITTLE ROCK

And oh yeah, this novel was prescient about COVID blah blah blah. I’m sure everyone has already talked about that, so I won’t bother bringing it up.

And some of them directly inspired the ones in LOST. For example, the aforementioned deaf guy is a big science-over-faith person and goes through very, very similar conversations and beats as Jack does in LOST. One of the villains simply follows Flagg because he’s the only one that will have him, just like Ben Linus with his own Man in Black. However, the most obvious instance of inspiration is the egocentric one-hit-wonder singer with destructive tendencies who needs to be forced by circumstance into becoming a good person and ends up choosing to sacrifice himself. This describes both Charlie and Larry.

The first book ends when a few individual viewpoints finally come together into big groups, but they’re still halfway to their final destination, so a couple new challenges like burst appendices crop up. It’s pretty much smooth sailing by then, though.

This short plotline was lifted wholesale by LOST, though it’s made a bit more interesting by the fact the doctor has to operate on himself. There are too many plotlines that are too similar and I have never seen elsewhere, but to describe a couple:

Dealing with moving dynamite that’s “sweating” nitroglycerin due to a hot environment.

A broken down car won’t start unless they push it down a big hill with the characters inside, take a leap of faith that they’ll be able to kickstart it before they crash against the bottom.

Though the LOST writers always had a fight between good and evil in mind, they were not inclined to share this at the beginning of the show, because the network (and they thought, the audience) would feel alienated by fantastical or sci-fi concepts. They had no excuse to take so fucking long, though, and I think seasons 3-5 failing to properly introduce the main conflict was money-motivated. The longer the true stakes stay hidden, the more seasons you can make.

"Darlton" eventually negotiated the end date for the series: a move that relieved a great deal of tension from the creative process. Thanks to him, the writers of Lost—myself not included, as I was long gone by then—were able to set a creative goal and truly steer the ship there without the need for the sort of dramatic stalling of which we were so frequently, and occasionally accurately, accused.

LOST also lifts this “bomb set up by the main villain kills half the cast” concept, but improves it massively in both execution, interactivity and thematics. The Man in Black, by Island Fiat, cannot directly kill any of Jacob’s Chosen Ones. So he sets up a bomb that will only actually go off if it gets defused, a trick to make them kill themselves. Jack, at last, is on the side of Faith, figures out the trick, and trusts the Island to not allow the bomb to go off. Sawyer is completely disillusioned after one of Jack’s mistakes killed his girlfriend, and chooses to try to defuse it. The bomb goes off, killing three important characters.

It also helps that this happens two episodes before the end instead of like 150k words, so the remaining plotline isn’t stretched with an anemic cast.

Stu managing to carry on despite everyone leaving him for dead and coming back to society with the help of a dog comprises a small survival-based coda to the book.

Oh yeah, there’s a magic dog who seems to always be able to guide people to safety, just like Vincent in LOST.

I’ve also found some essays here and there that make this one partially redundant, though they focus mostly on the most obvious reused templates like Charlie’s character above. I think I’ve made my additional case that there’s something more direct and pervasive to the connection, more than can be affixed to Hero’s Journeys and western character archetypes.

LOST’s ending definitely isn’t as bad as people say, but it’s not good. By the end, nearly every character has a pretty decent arc to them. But the sixth season as a whole is just poorly designed, doesn’t really play to the show’s strengths or mesh with character goals, and the answer to “what is the island” is ultimately vague and unsatisfying, feeling like less of a reveal and more of an “I’ll tell you more later”.

i absolutely love lost and wish there was more analysis of it online. this post is my personal brand of autistic heroin. i never finished the stand but your comparisons didn't seem at all contrived.

the stuff in season six was well foreshadowed imo, and built up to pretty well in season 5 at least. probably the final conflict wasn't planned far ahead of time but it felt quite natural as i was watching it. the temple arc was the only thing in it that annoyed me; it felt completely superfluous

I didn't think you were reaching, but I have never read The Stand or seen LOST, so your word was all I had to go on, and so you made it pretty convincing for someone with no preexisting feelings. I love this exploration of the threads of inspiration that can be traced through different works.