“How much is 9 times 6?”

“It is a mystery that is hidden from me by reason that the emergency requiring the fathoming of it hath not in my life-days occurred, and so, not having no need to know this thing, I abide barren of the knowledge.”

I’ve got to start using that.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court is one of those stories I’m sure most people have at least heard of, particularly those with interest in uplift1 and time-travel fiction, or maybe those who merely find extravagant author Mark Twain fascinating. He is a funny guy.2

But who actually reads it in the modern day? I fail to recall any particular plot details anyone’s ever mentioned to me. People bring up the name, sure, but if the story has kept a small level of cultural relevance, there has to be more to it than that. So I decided to give the novel a shot.

This story is from the same century as Dracula, subject of my previous review.3 In fact, they were written eight years apart.4 I suggest reading the section where I talk about flaws that can be hand-waved away by virtue of the times. Run-on sentences, weird formats, framing devices, Yankee’s got them all. And we must forgive Twain for it as we forgave Stoker.

Yankee starts with a little framing device that spoils the entire plot. A tourist is visiting an English castle and notices a bullet hole in one of the old armors, that a plaque identifies as surely done centuries after the fact.

The tourist hears a remark to the effect of “nah, I was there when that bullet was shot. In fact, it was I who shot it!” from a man he had only recently met—our main character. Fascinated by him, the tourist gets him to tell his life story.

The way he tells it, our protagonist, Hank Morgan5 was suddenly and without explanation transported from the nineteenth century West to sixth century England, and accosted by an armored, mounted knight.

Trying diplomacy doesn’t work, the man barely even understands his words. He’s instantly captured by the knight, and carried to Camelot castle for imprisonment. Arthurian Knights apparently just… do this. Glory is entirely built upon how many random miscreants you catch and imprison, even if they did nothing wrong.

Hank reaches the room of the Round Table and is initially amazed by the grandiosity, but soon disappointed by the details. King Arthur is a man with good intentions but no critical thinking about his place in the world, Merlin is a manipulative bore with little or no true magical ability, and Arthur’s court is no better than uneducated thugs.

Hank learns: he is to be executed tomorrow!

But we must learn to expect better from our protagonist. After all, his old occupation turns out to be superintendent at an arms factory, with plenty of hands-on experience as a blacksmith, inventor, chemist… honestly, he does whatever a 19th century man can, for Twain’s purposes.

From his jail cell, he shouts for a page, Clarence (who will quickly become his biggest supporter) and instructs him to take a message to Arthur.

I paused, and stood over that cowering lad a whole minute in awful silence; then, in a voice deep, measured, charged with doom, I began, and rose by dramatically graded stages to my colossal climax, which I delivered in as sublime and noble a way as ever I did such a thing in my life: "Go back and tell the king that at that hour I will smother the whole world in the dead blackness of midnight; I will blot out the sun, and he shall never shine again; the fruits of the earth shall rot for lack of light and warmth, and the peoples of the earth shall famish and die, to the last man!”

The king buys it. As he’s tied to the stake, with Merlin vowing to have him quickly executed despite the threat, Hank takes advantage of the total solar eclipse. He will bring the sun back if Arthur bows to his demands! He is really lucky,6 and the king is really stupid.

He doesn’t ask for riches, or for a way back to his time, which he’s skeptical they can provide anyway. He asks to become the right-hand man of the king. Lacking a better name, the peasants eventually settle on “The Boss” as the name for this new terrifying authority figure.

Most of the book thereinafter7 deals with The Boss’ attempt to uplift the Arthurian society into modern 19th century moral standards and technology.

In my experience boys are the same in all ages. They don’t respect anything, they don’t care for anything or anybody. They say “Go up, baldhead” to the prophet going his unoffending way in the gray of antiquity; they sass me in the holy gloom of the Middle Ages; and I had seen them act the same way in Buchanan’s administration; I remember, because I was there and helped.

The first quarter of Yankee is really hard to get through. I don’t know who said it, some old white guy probably, that all the best written works are crafted by people trying to say something about the human condition. The problem is, the story has nothing to say but “Dark Ages people dumb” until Hank gets on a horse and goes adventuring.

I got through it anyway. Throughout the novel, he never drops his rambling style of humor, like he’s giving a stand-up routine to every single person he’s talking to. And I say “he” instead of “his main character” because A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court is a self-insert in all but name.

Right before the novel properly gets going, a damsel in distress (Alisande, later just Sandy, later the Boss’ wife) is telling a chivalry tale to our main character. He spends a fair bit with her, since his first adventure involves saving her family from ogres, which turn out to be pigs and landowners respectively. He goes on this adventure because Arthur told him to get some field experience and heroic feats before a duel with a knight Hank offended. Take note of that, it will become relevant later.

But I digress. As Sandy tells it:

“—that Sir Uwaine smote Sir Marhaus that his spear brast in pieces on the shield, and Sir Marhaus smote him so sore that horse and man he bare to the earth, and hurt Sir Uwaine on the left side—”

“The truth is, Alisande, these archaics are a little too simple; the vocabulary is too limited, and so, by consequence, descriptions suffer in the matter of variety; they run too much to level Saharas of fact, and not enough to picturesque detail; this throws about them a certain air of the monotonous; in fact the fights are all alike: a couple of people come together with great random—random is a good word, and so is exegesis, for that matter, and so is holocaust, and defalcation, and usufruct and a hundred others, but land! a body ought to discriminate—they come together with great random, and a spear is brast, and one party brake his shield and the other one goes down, horse and man, over his horse-tail and brake his neck, and then the next candidate comes randoming in, and brast his spear, and the other man brast his shield, and down he goes, horse and man, over his horse-tail, and brake his neck, and then there’s another elected, and another and another and still another, till the material is all used up; and when you come to figure up results, you can’t tell one fight from another, nor who whipped; and as a picture , of living, raging, roaring battle, sho! why, it’s pale and noiseless—just ghosts scuffling in a fog. Dear me, what would this barren vocabulary get out of the mightiest spectacle?—the burning of Rome in Nero’s time, for instance? Why, it would merely say, ‘Town burned down; no insurance; boy brast a window, fireman brake his neck!’ Why, that ain’t a picture!”

Rarely you find a writer using his self-insert to praise his own writing style. I for one would have to disagree with Mark-boy here, because even the most beautiful prose can get tiring when you overdo it as much as he did during the first part of the book. Really, if he was such a great writer, why did he die anyway? Checkmate, Clemens.

More seriously, I’d say the fact that the events of Sandy’s stories were repetitive was the real issue there. No fanciful coat of paint can fix a story with no forward movement.

Perhaps hypocritically, Twain shows his own failings. Namely, having trouble giving characters unique, recognizable voices. He is not ashamed of this, even lampshading it when quoting a priest, “I remember every detail of what he said, except the words he said it in; and so I change it into my own words”. And this is not the only time he makes fun of himself:

“This is not good form, Alisande. Sir Marhaus the king’s son of Ireland talks like all the rest; you ought to give him a brogue, or at least a characteristic expletive; by this means one would recognize him as soon as he spoke, without his ever being named. It is a common literary device with the great authors. You should make him say, ‘In this country, be jabers, came never knight since it was christened, but he found strange adventures, be jabers.’ You see how much better that sounds.”

One of his biggest flaws as a writer, and he turns it into jokes, like Scatman John turning his speech impediment into his greatest musical strength, or like my turning my meme knowledge into this paragraph.

Over time, Twain must have realized that the gimmick of a 19th century man telling poor uneducated people they were dumb was getting old, because Sandy finally gets back at him. She berates him over his habit to lord over her a mastery of modern concepts, which she could not possibly know herself, being a random sixth century girl. Hank realizes his mistake, and he becomes a more down-to-earth character after that.

After that rocky start, A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court becomes a story about the ideals of Enlightenment versus the ideals of the Establishment. At the time, that was apparently the Catholic Church and nobility in general.

The writer feels very strongly about this:

Well, it was a curious country, and full of interest. And the people! They were the quaintest and simplest and trustingest race; why, they were nothing but rabbits. It was pitiful for a person born in a wholesome free atmosphere to listen to their humble and hearty outpourings of loyalty toward their king and Church and nobility; as if they had any more occasion to love and honor king and Church and noble than a slave has to love and honor the lash, or a dog has to love and honor the stranger that kicks him! Why, dear me, any kind of royalty, howsoever modified, any kind of aristocracy, howsoever pruned, is rightly an insult; but if you are born and brought up under that sort of arrangement you probably never find it out for yourself, and don’t believe it when somebody else tells you. It is enough to make a body ashamed of his race to think of the sort of froth that has always occupied its thrones without shadow of right or reason, and the seventh-rate people that have always figured as its aristocracies—a company of monarchs and nobles who, as a rule, would have achieved only poverty and obscurity if left, like their betters, to their own exertions.

The most of King Arthur’s British nation were slaves, pure and simple, and bore that name, and wore the iron collar on their necks; and the rest were slaves in fact, but without the name; they imagined themselves men and freemen, and called themselves so. The truth was, the nation as a body was in the world for one object, and one only: to grovel before king and Church and noble; to slave for them, sweat blood for them, starve that they might be fed, work that they might play, drink misery to the dregs that they might be happy, go naked that they might wear silks and jewels, pay taxes that they might be spared from paying them, be familiar all their lives with the degrading language and postures of adulation that they might walk in pride and think themselves the gods of this world. And for all this, the thanks they got were cuffs and contempt; and so poor-spirited were they that they took even this sort of attention as an honor.

Let us know what you really think, Clemens!

You see my kind of loyalty was loyalty to one’s country, not to its institutions or its office-holders. The country is the real thing, the substantial thing, the eternal thing; it is the thing to watch over, and care for, and be loyal to; institutions are extraneous, they are its mere clothing, and clothing can wear out, become ragged, cease to be comfortable, cease to protect the body from winter, disease, and death. To be loyal to rags, to shout for rags, to worship rags, to die for rags—that is a loyalty of unreason, it is pure animal; it belongs to monarchy, was invented by monarchy; let monarchy keep it. I was from Connecticut, whose Constitution declares “that all political power is inherent in the people, and all free governments are founded on their authority and instituted for their benefit; and that they have at all times an undeniable and indefeasible right to alter their form of government in such a manner as they may think expedient.”

Under that gospel, the citizen who thinks he sees that the commonwealth’s political clothes are worn out, and yet holds his peace and does not agitate for a new suit, is disloyal; he is a traitor. That he may be the only one who thinks he sees this decay, does not excuse him; it is his duty to agitate anyway, and it is the duty of the others to vote him down if they do not see the matter as he does.

Please, no more. We get it. (Imagine Mark Twain’s Twitter account!)

At one point, he visits Morgan Le Fay, evil witch extraordinaire, who abuses her power at every possible point—such as having a composer hanged for playing a bad piece of music at her feast. Of course, Morgan is terrified of The Boss, who among his current feats has the invention of dynamite and, of course, the banishment of the Sun itself.

The poor queen was so scared and humbled that she was even afraid to hang the composer without first consulting me. I was very sorry for her—indeed, any one would have been, for she was really suffering; so I was willing to do anything that was reasonable, and had no desire to carry things to wanton extremities. I therefore considered the matter thoughtfully, and ended by having the musicians ordered into our presence to play that Sweet Bye and Bye again, which they did. Then I saw that she was right, and gave her permission to hang the whole band.

It is amusing, but I can’t help but think moments like these stop Yankee from delivering its intended message to the reader. They have trouble coexisting with an arc in which the main character is sold into slavery and vows to reform the social order.

Slavery is where the story is going next, in fact. While The Boss has already been modernizing England by introducing toothpaste and top hats in-between helping damsels, that’s not enough for him. King Arthur is intrigued by The Boss’ intention in dressing up as a peasant and experiencing the troubles of a fellow man, and decides to join him.

Hank loves the idea. The issue is that the King is really, really bad at acting like anything other than a king:

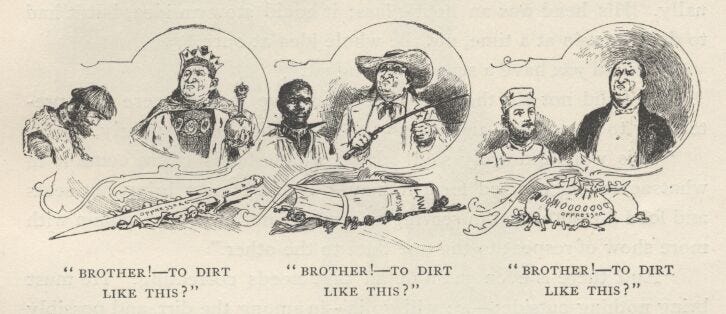

“Now, sire, imagine that we are at the door of the hut yonder, and the family are before us. Proceed, please—accost the head of the house.”

The king unconsciously straightened up like a monument, and said, with frozen austerity:

“Varlet, bring a seat; and serve to me what cheer ye have.”

“Ah, your grace, that is not well done.”

“In what lacketh it?”

“These people do not call each other varlets.”

“Nay, is that true?”

“Yes; only those above them call them so.”

“Then must I try again. I will call him villein.”

“No-no; for he may be a freeman.”

“Ah—so. Then peradventure I should call him goodman.”

“That would answer, your grace, but it would be still better if you said friend, or brother.”

“Brother!—to dirt like that?”

“Ah, but we are pretending to be dirt like that, too.”

“It is even true. I will say it. Brother, bring a seat, and thereto what cheer ye have, withal. Now ’tis right.”

He manages, somewhat, and we get to the best part of the book. It’s already pretty evocative, a modern(ish) man and a King trying to pose as villeins to learn their plights, but the writing also becomes more refined, and the egalitarian themes are reflected strongly in this arc.

Hank is filled with admiration, even though the King is kind of an idiot, as he enters the house of a dying woman with smallpox. He helps her see her (deceased) family one last time by personally taking their bodies to her, as one final nicety, no matter that the Church banned everyone from interacting and the risk of getting infected.

The King and Hank go through pretty much every bad experience of the poor, but The Boss gets tired, stops their adventures and suddenly decides to show off to some wealthy peasants for some reason, by buying them a lavish banquet and enumerating how much each item costs.

I paid no more heed than if it were the idle breeze, but, with an air of indifference amounting almost to weariness, got out my money and tossed four dollars on to the table. Ah, you should have seen them stare!

The clerk was astonished and charmed. He asked me to retain one of the dollars as security, until he could go to town and—I interrupted:

“What, and fetch back nine cents? Nonsense! Take the whole. Keep the change.”

There was an amazed murmur to this effect:

“Verily this being is made of money! He throweth it away even as if it were dirt.”

The blacksmith was a crushed man.

I still don’t understand where Twain was going with this—is he making a point about smug rich peasants that nonetheless pale in comparison to someone like The Boss? Did he just want to explain to the reader the difference between true wealth and merely having more money?8 Kind of mean-spirited considering the rest of the book. It gets out hand quickly, as the Boss jokingly accuses them of treason for a technicality, which they take very seriously, erupting into a fight.

I cannot overstate how confusing that whole chapter was.

They quickly escape before it becomes a bigger thing. As they reach a major town, the King and Hank fall for one of the classic blunders—being mistaken for slaves and having no proof of not being slaves. You’d think this would be the darkest arc of the book, with The Boss at his most desperate, to the point of brutally attacking a man to escape—who turns out to be a random guy instead of their slave driver—and get word out to Clarence at Camelot through a secretly installed telegraph network. As he waits for rescue, Arthur himself has no choice but to murder the slave-master himself, and frees everyone else.

The climax of this little arc is reached. The Boss is recaptured and set to be hanged with the other attempted escapees. Turns out, his fellow slaves sold him out to the guards, because they didn’t want him to go free when they were captured themselves, in a fucked up crab-bucket style situation.9 All seems lost, the knights are too far way to get the horses ready and reach them in time.

Luckily, Clarence comes through, with Lancelot and his knights riding bicycles to the city!

For a second, I really thought the story would end with Arthur being hanged as a slave, the ultimate tragicomic fate for someone who embodied the status quo. It would have said something, and been better than the ending we ended up getting.

Anyway, they return to Camelot. It’s time to settle the duel with that knight he offended 300 pages ago.

In a shocking display of power-fantasy isekai self-insert writing, The Boss lassoes the knight to the ground and fucks him up with a revolver—readers will notice this is the source of the bullet hole at the beginning of the story—then kills every single knight that challenges him after that.

Bang! One saddle empty. Bang! another one. Bang—bang, and I bagged two. Well, it was nip and tuck with us, and I knew it. If I spent the eleventh shot without convincing these people, the twelfth man would kill me, sure. And so I never did feel so happy as I did when my ninth downed its man and I detected the wavering in the crowd which is premonitory of panic. An instant lost now could knock out my last chance. But I didn’t lose it. I raised both revolvers and pointed them—the halted host stood their ground just about one good square moment, then broke and fled.

And that’s that for the duel, and for anyone willing to ever challenge The Boss again. Time for a timeskip.

This paragraph comes from much earlier in the novel, but let’s pretend it came after the above scene:

Something of this disagreeable sort was turning up every now and then. I mean, episodes that showed that not all priests were frauds and self-seekers, but that many, even the great majority, of these that were down on the ground among the common people, were sincere and right-hearted, and devoted to the alleviation of human troubles and sufferings.

Finally, Mark Twain’s character arc is complete. His Author Tract has been defeated, and he’s finally realized the outgroup is not necessarily always evil. I for one can not wait for the final part of the novel where all these themes will be reflected and resolved to a reader’s satisfaction, with more measured main character and villains at the helm.

…Nah.

In the final part of the book, the Catholic Church poisons Hank’s daughter and tricks him into leaving the country so she can recover via Healthy French Air, well-known panacea. Then, over the next three years, they demolish everything he’s created, kill the reformed King Arthur, and take over.

Hank learns this soon after getting back to the country and finding a few dozen hidden conspirators headed by the newly hypercompetent Clarence, waiting for his return. The rest of England has been fully taken over by the Church. Not one of Hank’s lessons or technologies sunk in.

The Church discovers he’s back. After a tense battle, Hank and Clarence conveniently blow up all their factories as traps for the Church’s soldiers, and officially bury the age of chivalry and knights. However, it’s a bittersweet victory, for they’ve sent the country to the Dark Ages again. To really turn things for the worse, Merlin sneaks in, dressed as a woman, and for once pulls out a spell that actually works—putting Hank to sleep for thirteen centuries10.

He wakes up in the present day, and right after telling his story to a stranger and making the novel go full circle, succumbs to a mysterious disease and dies. His final thoughts are joyful—he’s going to reunite with his wife and daughter in Heaven.11

I firmly believe Twain wrote himself into a corner here—by consequence of his own prologue, Hank had to somehow survive alone into the modern day, and that could not happen if wizardry was fake after all. Personally, I would have just released the book without a prologue and with a better ending. Screw paradoxes, I would have liked to see The Boss’ techno-medieval world. I would have liked a reformed Arthur helping him with it. Hell, I would have even enjoyed a Merlin redemption arc. The story went way too hard on him for no reason.

I cannot stress this enough, this ending ruins the entire story. You can either have a serious high fantasy tragedy, or a wacky comedy about staging an industrial revolution under King Arthur’s nose. Similarly, none of Hank’s attempts to enlighten the plebs seem to amount to anything. The Church continues to have infinitely arbitrary power even when the brunt of the story was spent on having The Boss reduce their sphere of influence. The writer put a bunch of conflicting ideas into Yankee, and there’s the inevitable result: a huge mess.

Is this why people never recommend this story anymore, I asked myself when I reached the last page and saw that yes, this was the ultimate conclusion to all of Hank’s adventures—his entire family dead, the Church taking over, all his progress erased.

It fucking sucks. At least the brunt of the story was really funny,12 so it doesn’t feel like a waste of my time, only a waste of potential.

A funny story about antiquity, itself an antique. 6/10

You will like this book if you love: funny jokes, situation comedy, wordplay, uplift, isekai, the nineteenth century, knowledge-is-power-fantasies.

You will dislike this book if you hate: author tracts, smugness, white savior complex, inaccurate historical facts,13 bad endings and pacing.

You will love this book if you hate: The Church!!!

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court is available at Project Gutenberg, in beautifully illustrated form.

Uplift is a recently popular genre where a modern human brings technology and other cultural knowledge-say, medical practices, like in Castle Kingside-to a less advanced society. You often see this with time-travel stories, but Uplift stories focus on the process of training the people, spreading the tech, etc. I’ve actually had trouble finding that specific definition online (I guess this is close), but the genre is well known in my circles.

And yes, Andrew Hussie was very, very obviously inspired by Mark Twain’s humor, the homages in the TNG Edits and Homestuck were not ironic nor coincidence, as I soon found out. If only he had Twain’s morals.

This was a complete coincidence, too, I had no idea until I looked for the dates just now.

I felt like a bad reader for not remembering his name, but the entire thing is written in first person and apparently the name ‘Hank’ is only in there twice.

I expected at one point we’d get some kind of explanation as to why he was sent to one day before a total solar eclipse he, for some reason, knows the exact date of. He’s not even an astronomer! We never get a justification. Some isekai protagonists get a smartphone, this guy got astro-serendipity.

Fuck off spellcheck, it’s a real word.

I assign high probability to my missing some subtext here, maybe something only a 19th century man would understand.

This is surely not social commentary in any way whatsoever.

What the hell is the deal with Merlin anyway? The entire rest of the story tells us how incompetent Merlin is, he can’t even make a single spell happen, and as the readers we’re led to believe that magic has never existed. And what is with three-year timeskips ruining stories anyway? Homestuck, Worm… It’s happened way too often to be a coincidence.

Oh no, Hank has won the victory over himself. He loves the Catholic Church!

I’m sure it was even funnier in Twain’s time, which I suppose was filled with the kind of garbage generic knight tales Sandy told. I am after all reading a work well after the culture it’s responding to died.

I was as surprised as Twain would have been to learn droit du seigneur was probably never a real thing.